I learned about the healing process early.

The first fourteen years included two brothers, then a sister.

My dad used to tell us to “quiet down, there’s a sick man in the hospital.”

In North Bend, Oregon, the hospital was about a mile and a half from our house. We weren’t that noisy.

After a tree climbing accident, there was a sick kid in the hospital and I didn’t hear a thing.

That was my one and only time overnight in a hospital until last week.

Climbing trees was a recreational activity where I grew up. Older brother, by about a year, and I used to climb the big alder tree in the neighbor’s backyard.

On windy days we’d climb high enough to feel it sway. Very daring boys.

The top was split into two branches where the most brave would sit and hang on.

One blustery morning we raced to the tree to get to the top first. Big brother led, but I was catching up.

Half way to the top I remember grabbing a branch stump and pulling up.

The story I heard in the hospital was that it was a rotten branch stump and broke when I hoisted myself up.

I remember the stumpy part, but nothing else.

I fell, bounced off a few branches on the way down, and landed on a pile of construction debris at the bottom.

Brother raced down, got our dad, and he called the ambulance.

First Hospital Healing Process

I woke up stiff and bruised but not broken in major places.

My left hand was wrapped with two tongue depressors sandwiching my broken ring finger.

No broken neck, back, or leg. Just a finger. How lucky was that?

A hospital room in 1965 didn’t have a TV, video game console, or anything not associated with the healing process.

To help me while away the time my parents brought me two wooden block puzzles that breakdown into dozen pieces. One was a square, one was barrel shaped.

I remember them because I couldn’t take them apart or put them together with one hand. It was the thought that counted, right? Some people have fading memories, not me. The room was painted pale green.

Eventually I got a splint on my finger and release papers. It was my second broken bone and not my last. My collar bone had snapped the year before kindergarten during a game of Swinging Statue.

That’s where the biggest kid swings smaller kids in a circle and lets them fly. You scored points if you landed and didn’t move. Who makes up these games?

I landed on a sidewalk curb and couldn’t move, so I won. My prize was a broken collar bone, the same one I broke in sixth grade.

That time I flew over the handlebars of a bike when the kid I was riding on the crossbar didn’t want to go fast and stuck his foot in the front spokes for the launch. He was okay after I unwound his leg from the fork. That’s when I felt my break.

My dad felt it when he dropped off my big tenor saxophone and I couldn’t lift the case.

Fifty Four Years And One Hospital Later

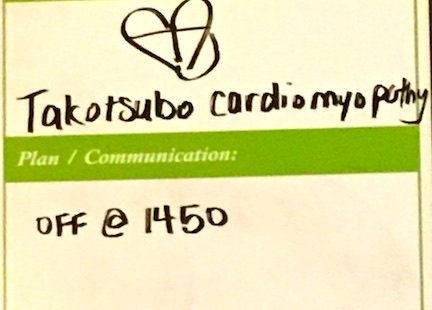

Last week I checked myself into a hospital for the second time. My condition turned out to be a broken heart, which sounds romantic, doesn’t it?

Things kicked off in Charleston, Oregon. I probably should have picked up a couple of wooden block puzzles and checked into the Bay Area Hospital.

After growing up in North Bend I’d had my heart broken plenty of times. Or so I thought.

Friendship rings and half-heart necklaces, exchanging named bracelets, all had the super-charged expectations of something, but what?

After learning about life in Philadelphia and Brooklyn and Delaware, the ‘what question’ about expectations came into better focus.

The clarity sharpened about whose heart gets broken after moving to Portland from Brooklyn. Some move. Three days on a $100 Greyhound ticket to anywhere from Port Authority on Manhattan’s westside.

If I had a broken heart in those days the healing process worked

Then I met THE ONE, I met HER, and we married the heck out of each other.

She’s the one who drove me to the local hospital, sat in the emergency room with me stretched out on a gurney, and went home after they wheeled me off.

I watched the ceiling and walls pass by like a movie and I was the reluctant star. Once I took up residence in a hospital room the real stars came out.

With IVs jacked into both arms, electrocardiogram contacts pasted to my chest, defibrillator pads glued to my back, and an automatic blood pressure cuff pumping tight every fifteen minutes, I understood why it’s called intensive care.

There was a TV with a remote but I left it off and thought about the last time I’d been in a hospital room. I looked at my crooked ring finger and the golden ring on it.

The healing process was already in full swing with the technical drawing in the top image.

If I could make a nurse laugh, and they draw that, I knew I’d be okay.

My wife picked me up Tuesday morning after a long night. She’s still The One.