Comparison culture didn’t start with social media, but that’s where it found fertile ground.

Baby Boomers and every generation before, all had the same comparison:

My Dad is better than your dad.

What comes after that? Maybe a fight.

Who hasn’t had comparisons?

You compared to your older brother, your younger brother, your sister and all your cousins?

Everyone gets compared but don’t know it. Why?

Because some people have manners.

It’s not necessarily bad manners if you share your comparisons.

You probably won’t have friends or family around to share with, so if you’re comfortable being the ranting crank sitting on a park bench, go ahead.

The updated version is the ranting crank sitting behind a keyboard.

In the first example your audience consists of passers by, pigeons, and other yackers.

In the second it’s the online world, which increases the odds of finding people who share your feelings.

Now you’ve got a movement.

What’s it like to go from throwing shit at the wall to see what sticks, to mentoring others with your vast experience?

I’ve heard ex-cons talk about prison as criminal graduate school.

You’re not good enough at crime to avoid prison, but you learn better tacticals from guys further advanced in their crime careers.

Is there a better way to get rehabilitated?

In the comparison culture I put crime school up against my crime interview.

My best friend in New York wanted a different life.

We met in the Army. His last job was street manager for a popular disco, the door man keeping the line in order.

He wanted a different life and joined the Army, but he had a bad experience and got his discharge before one hundred and eighty days and went back to the disco.

He liked party people better than enlistees. I visited him on weekends. He had a sweet gig compared to the Army.

Bad Experience Compared To A Bad Experience

The thing that took him out of the Army was shot practice.

Not gun, needles. We were in medic school.

When shot practice day came around he fainted. Didn’t like the needle.

Who does? I’ve given shots and drawn blood plenty of times. Creeps me right out, but I did it.

My buddy presented his case and got out. This was 1974, a rebuilding year, and they wanted people who wanted to be in the Army.

He returned to the New York streets, to a club across from the old Dangerfields.

I took the train up from Philadelphia after work probably ten or fifteen times on Fridays and stayed until Sunday, hanging out in a wild scene.

Since we were the same size I wore his New York clothes to fit into the bar scene, if not the dancing, and drank for free as a guest of the house.

My buddy introduced me to the managers and bosses and got me thinking about my after-Army plans.

Comparison Culture would pit going back to college in Oregon, or learn the ropes in the Big Apple.

One Thursday I called to tell him I’d be up there the next day and the call was routed to the club.

The guy there said my pal was in the hospital and gave me the number.

Gary: Come on up. I’ll give you the key to my place so come to the hospital first.

He’d had an incident.

A drunk regular wanted to get in and wouldn’t let it go.

After he fell, got punched, kicked, all in front of his drunk girlfriend, he sent a group over to get even after hours.

My guy got stabbed, nearly bled out, and there he was in a hospital bed telling me all about it.

I moved away from the window.

If the guy didn’t like needles, no way he liked knives, but he was toughing it out.

The Crime Interview

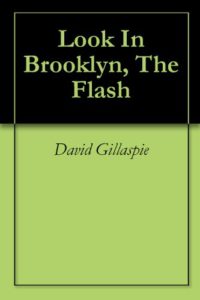

I moved from Philadelphia to Eugene, Oregon for two years, then headed east again, landing in Brooklyn.

I called the Adam’s Apple. Gary didn’t work there anymore, but they gave his number to an old friend.

He drove out to my place and picked me up. We went to his new place, not far from the club he didn’t work for.

I told him what I’d been up to, dropping out of college, getting engaged, working construction.

The most down to earth blue collar time was the summer I carried cement foundation blocks and mixed mud for a masonry company building a shopping center in Delaware.

The work was hard and I took to it with a vengeance to be the best hod carrier they’d ever have.

I did the work of two men and asked them to fire the slacker they hired after me and pay me more.

But the slacker was a neighbor’s kid and they couldn’t fire him.

After four months of navigating the dirt mounds left from excavation and footings I was living the hard life with an eye toward the soft life.

The crew worked hard all week and did side jobs all weekend, then drew unemployment all winter.

But they wouldn’t pay their boy what I was worth.

I’d proven myself with the bricks, the cement mixer, driving the deuce and a half truck, but not taken seriously enough to see a future with me on the crew?

Positive, can-do, attitude; no complaining about the work load; eager to learn new things.

Just not worth an extra fifty cents an hour.

The Outfit

To join the outfit you need to be versatile; you need to understand value.

If you’re going to hijack semi trucks full of cigarettes, you to know the split gear box.

If you get pulled over driving a semi full of cigarettes in Florida, you need to be comfortable with snakes and gators while you flee the scene through a swamp.

To fill a list of wants, you need to target the right people so no one gets hurt.

Maybe it’s jewelry, or money, there’s always something else.

That chunk of gold? It’s a cigarette lighter worth thousands that came with another job.

It sweetens the pot.