Call the medic when there’s something wrong, anything at all.

MEDIC.

Right here, pal. Calm down.

All better? Good.

In the mid-70’s I was a trained Army medic with an office on Oregon Avenue in Philadelphia.

That I was actually from Oregon was a funny coincidence with the staff.

Every morning my waiting room was full of civil servants, retired military, and active duty on temporary assignment.

Ten to fifteen people a day waited on me for their height, weight, pulse, BP, hearing, vision, and EKG before moving on to the doctors.

In the front office sat a red phone, a hot line, to call the medic. I was also the ambulance driver.

When it rang it meant drop everything, grab a doctor, and go.

One day it rang for some guy having a heart attack in his own office that turned out to be indigestion, but at the time it was deemed an emergency.

We gave him the business, loaded up, and transported him to the local hospital.

A week later he stopped by to say thanks.

Since it was a slow afternoon I asked him about his life.

He was a double-dipping civil servant in logistics after he retired from the Army as a supply chain guy.

I was a PFC complaining about a backwater clinic in South Philly.

He told me I reminded him of someone he knew from WWII.

The Sergeant’s Report

I met Robert during the first crush of enlistments after Pearl Harbor.

My assignment at Fort Dix was finding guys smart enough to become airplane mechanics.

Those who failed in my classroom went to infantry school.

It was all about testing in the beginning, and how fast the students could pick up the basics of engines and electronics.

Robert passed the tests with extra credit. He’d finish first then doodled on the test sheet.

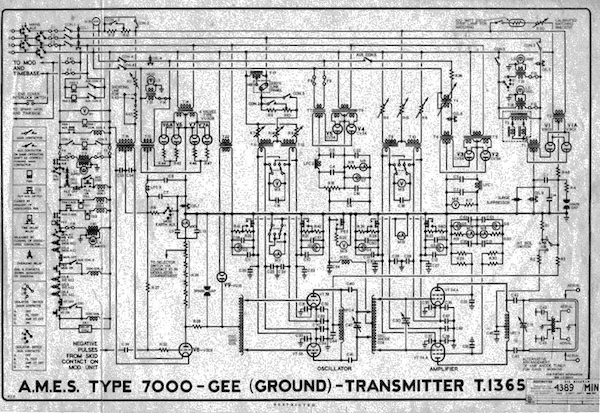

The kid drew electrical diagrams I’d never seen, beyond the books and everything else.

I asked around and learned he was a college boy, a fancy college boy.

Instead of promoting him up the education ladder, I kept him around to help with class after his group had moved on.

Also to learn a few things myself.

One day the instructors got a message about a missing person, some rich man’s son who’d secretly joined the Army.

His daddy wanted him back.

I asked Robert if he knew anyone like that, and if he did I could help.

He asked how I could help.

I told him I knew people in back-channels who recruited the best and brightest.

That’s when I asked him about his electrical diagrams.

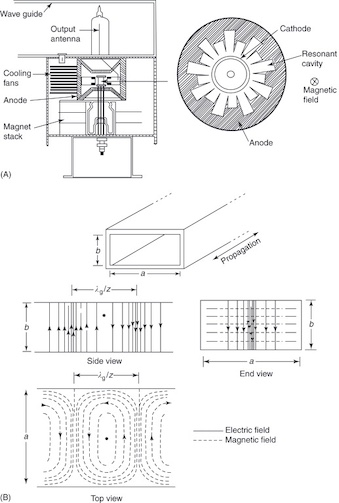

Robert said he was working on perfecting the cavity magnetron for micro-wave radar.

Along with that, he said he’d learned how to boost conventional radar.

So I put him in the back-channel so he wouldn’t be found and returned to his daddy’s laboratory.

Winning WWII With Radar

The kid disappeared, but my network got back to me.

Robert was our secret weapon as long as no one knew about him.

It was tight network of people who knew how to jump hurdles, and the Army had plenty of dumb hurdles.

Back then it was the Army Air Force and Robert followed the planes from Guadalcanal to Tinian and every stop in between.

The pilots loved him and the mechanics weren’t sure what he did.

But they knew the planes he worked on had a better chance of making it back after a mission.

I caught up with him in the Northern Marianas when the B29’s started fire bombing Japan.

Robert was on board when they took off for Tokyo.

Sixty-seven times the bombers flew over Japanese with their payload of death and they all wanted Robert’s approval before taking off.

He gave it by tuning up their radar for maximum range. No one could figure it out.

By the time the new planes arrived for special missions, Robert was the go-to guy before takeoff.

He flew with them over Hiroshima, then Kokura, and Nagasaki.

After the war ended and everyone packed for home, Robert was one of the last to leave the island.

His research work never stopped and he had folders of diagrams and models that he continued filling.

He stayed in the groove until the last plane left, then jumped on.